Rewind Record Review: Aztec Two-Step

An unrelenting horizontal mist tickles the nostrils, as artisan bakers meticulously shuffle smorgasbords of chocolate lava hotcakes and strawberry bran muffins, free at last from gluten’s tyrannical yoke. Down Brooklyn Ave, a short stroll from the University of Washington campus, Seattle’s Mossy Bottom Records flashes Ray Davies’ Village Green mantra: “Preserving the old ways / from being abused / protecting the new ways, for me and for you.” Now if that don’t get in the mood to buy some vinyl, what more can we do?

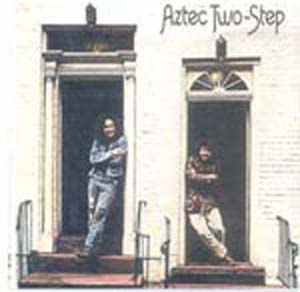

With the grooves of my favorite Simon & Garfunkel LPs wearing thin, I’m on the lookout for a folk tandem with a mischievous smile and hair to match. After just twenty-two seconds of alphabetical probing, there’s Aztec Two-Step’s Rex Fowler and Neal Shulman smirking at me through adjacent darkened doorways. Fowler, donning ripped denim trousers and a faded jean jacket, crosses his arms as he leans causally against a chartreuse doorframe. Atop a crumbling maroon staircase and thin black railing, the mustachioed Shulman, resting on one leg in perfect symmetry to his pal next door, rocks a disheveled Afro, second only to glam rocker, Marc Bolan.

Aztec Two-Step’s 1972 self-titled debut gets underway by ripping a page right out of the Zen-laden Tassajara Bread Book. Making and Baking, channeling Tassajara’s manifesto of culinary independence and retreat from homogenous corporatism, portrays an impenetrable sanctuary of two. Amidst crisp acoustic guitar, Fowler and Shulman gently purr: “You do the bakin’ and I’ll do the makin’ / how our lives will rhyme / yes you do the bakin’ and I’ll do the makin’ / spinnin’ and singin’ together.”

Named after a line from San Francisco beatnik Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind, Aztec Two-Step formed fortuitously when Fowler and Shulman met at a Boston coffee house open stage. A few months later, the band was signed to Elektra Records and cutting a record.

Rattlesnake shaker ushers Fowler’s triumph of transience on Kerouac-inspired The Persecution and Restoration of Dean Moriarty (On The Road). In a phantasmagoria of hollow patriotism and jarring hedonistic impulses, Aztec Two-Step belts the striking, fiery tale of ramblin’ man Neal Cassidy: “He was born on the road in the month of July / and he’ll live on the road ‘til he sees fit to die / ‘cause he learned on the road how humanity cries / how society lies, he sees with more than his eyes.” Though perturbed and flustered by this renegade iconoclast’s ways, Fowler exposes submission and complacency as America’s true miscreation: “So you’re curious ‘bout this man who I speak / ‘cause he tears you and scares you out of your sleep / I am sure that you’ll find, if you open your mind / that it’s you and not he who is really the free-he-he-heekkkk!”

A smooth, fluid Spanish guitar akin to Al Stewart’s Year Of The Cat propels Infidel. On So Easy, which sounds like a Peter & Paul track sans Mary, bluegrass banjo and blithe harmonica set a scene of blue skies and effortless, idyllic love. Prisoner features a deftly navigated tempo shift, as the two singers bellow in unison, “Bring me home!” Clanking guitar and sturdy baseline on Almost Apocalypse set the stage for inward retrospection and our endless quest for authenticity: “I was outside in the alley / I was searching for the truth / when I came upon a vision / of myself in early youth.”

Perhaps because the titles of Aztec Two-Step’s follow-up LPs sound like something out of a Christopher Guest flick (Second Step, Two’s Company, Adjoining Suites), none attracted the cult following of their first record. Aztec Two-Step’s 1972 self-titled debut builds on bedrock 60’s social currents of broad solidarity, escapist modernism, and a double scoop of flower power serenity. And although Fowler’s majestic ‘fro has faded into a reflective bald dome, the band’s still “On The Road” and going strong!

0 comments